How does a small, family owned quarry company compete with giant corporations? It’s the pits.

Business North Carolina, June 1999

By Edward Martin

On the floor of the 100-acre pit, Johnny Bratton slows as a quarry truck rumbles by, towering over his Land Rover. Behind him, a granite cliff rises like a canyon wall, and in front, stone terraces turn from gray at the bottom to motley yellow in sunlight at the rim.

On the floor of the 100-acre pit, Johnny Bratton slows as a quarry truck rumbles by, towering over his Land Rover. Behind him, a granite cliff rises like a canyon wall, and in front, stone terraces turn from gray at the bottom to motley yellow in sunlight at the rim.Wake Stone Corp. began here in Knightdale, just east of the Neuse River, in 1970. “Dad and I were walking, and there were some outcroppings in the fields and along the edge of the woods that indicated rock close to the surface,” Bratton says. His father bought the land, and a quarry was born.

Stillborn, almost. His dad, John Bratton Jr., had quit as an engineer and vice president at aggregate producer Martin Marietta Inc. in Raleigh to start the quarry. With only $50,000, he was low on capital. On the road in, Johnny Bratton nods at a restored, three- room tenant house with a red roof and tan paint. “Our first world headquarters.”

When Martin Marietta learned of the plans, it quickly reopened a nearby quarry, still remembered at Wake Stone as an attempt to crush Bratton for leaving. “They poured everything they had into it, and we had three guys over here,” says his son, who was one of them. “It was pretty demoralizing.” He pauses. “But it didn’t work.”

Nearly three decades later, in an industry in which Vulcan Materials Co., Martin Marietta and Hanson Materials PLC rake in 60 cents of every dollar spent on Tar Heel rock, Wake Stone is the largest independent still standing. It has four quarries, all in

North Carolina, which will generate revenue of more than $35 million this year. That makes it the fourth-largest stone company competing in North Carolina but tiny compared with its billion-dollar competitors.

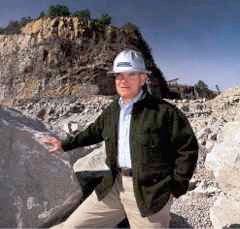

At 52, Johnny Bratton, now CEO, no longer has the mod haircut and college grin of the ’70s, when he mugged for a photo with crane operator Frog Burnette. He has the serious demeanor of an engineer and oldest son entrusted with the family business. Grappling with why the company has refused to bow to competition or buyout offers, he recalls those early days. “Maybe being the underdog hasn’t been all bad.”

At Wake Stone, survival has become corporate culture. The company has to be scrappier and more efficient and make do without. When a quarry manager wants a letter typed, he does it himself. Revenues have more than tripled since 1990, but the work force of 140 is essentially unchanged. Only two executive posts have been added.

In the late afternoon sun, Johnny Bratton stops beneath a five story rock crusher, fed by miles of conveyor belts loaded at the pit bot- tom by $600,000 shovels and $450,000 Caterpillar trucks. A quarry like this costs Wake Stone $10 million to open. Bratton and staff design and build their plants themselves, saving a third of the cost.

The effect: When suitors call, Wake Stone can afford to say no. Company executives say they’ve been approached by buyers from as far as the United Kingdom and Australia. “The big boys,” says John Poole, vice president for sales, “would still very much like to be rid of us one way or another.”

“Consolidation is the trend of the 1990s, and aggregates is the class example,’ says Jack Kasprzak Jr., a Scott & Stringfellow Inc. analyst in Richmond, Va., who tracks Birmingham, Ala.-based Vulcan, the nation’s top aggregates producer with $1.7 billion in 1998 revenues, and Martin Marietta, No. 2 with $1.1 billion. “Martin Marietta in particular has been buying right and left.” But it hasn’t made a bid for Wake Stone. Kasprzak and others believe that would trigger antitrust response because of overlapping territories.

Size makes sense in the stone industry. At about $7 a ton in the Triangle, rock is dirt cheap and quarry margins slim. Location is priceless, considering it costs $1.15 to move a ton of stone a mile. The result is that Wake Stone and other quarries are an odd mix of mining, manufacturing and retailing. There’s no delivery. Road builders, contractors and others send their own trucks.

Quarries compete furiously for sites close to big highways, with the right zoning, right neighbors and right rock. That’s where Wake Stone is at a disadvantage to deep-pocketed competitors. “They can buy up sites and let them sit for 20 years,” says Tom Oxholm, a Wake Stone vice president and accountant. “We can’t.”

At Martin Marietta, Stephen Zelnak Jr., chairman and CEO, kicks in his own set of numbers. “If you look back two years, the top five players had 17% of the nationwide market. Today it’s closer to 25%. But there’s room for some strong regional players, and I’d consider Wake Stone one of those.” Zelnak, who joined Martin Marietta long after its early attempt to derail Wake Stone’s startup, has a healthy respect for his small rival. “They’re smart, tough and professional. The key strategic variable in aggregates is location, and they’ve done a great job of establishing locations in growing areas.”

That was high on the list of priorities when John Bratton Jr. And his son were stomping through the brambles of eastern Wake County looking for good rock 29 years ago. Still chairman, the founding father of Wake Stone is now 76, bald, shorter than his sons and with the hand- shake of a former Marine, which he is.

After building roads and airports in China in World War 11, Bratton returned to Raleigh in 1946 to join Superior Stone Co., forerunner of Martin Marietta, as an engineer. By the late 1960s, oldest son, Johnny had switched from a premed major at UNC to his father’s alma mater, N.C. State, and a civil- engineering degree. Between Raleigh and Durham, 5,000 acres of pine woods were taking on a new identity -Research Triangle Park. It would trigger the largest concentration of building and highway construction in North Carolina history. While the impact on the region was becoming clear, the senior Bratton was getting restless at Martin Marietta. “Dad wanted for some time to have his own business, but he also very strongly wanted to create something of value for his children in the future,” says Johnny Bratton.

East of Raleigh, just before Piedmont granite starts to give way to soft limestone of the coastal plain, John Bratton found a site. It was owned by an old farmer whose son still lives in the now showplace farmstead, tending the grounds and minding the Brattons’ horses. But before the Brattons could set up their first conveyors and crushers, Martin Marietta was rolling stone out of its reopened pit.

Early on, John Bratton took minimal paychecks or none at all. “I was an hourly employee in those days, so I wasn’t smart enough to realize how hard it was,” says Johnny Bratton. But the Brattons had an ace in their deepening hole. Several customers, including Ready Mixed Concrete Co. of Raleigh, promised them business. A former Ready Mixed executive says builders feared they’d have no leverage over prices if only one stone company was serving the area, and they didn’t like Martin Marietta’s tactics. “The customers saw what was happening and stuck with us,” says Johnny Bratton. After only two years, Martin Marietta closed its quarry there.

Tied to the cycles of construction and recession, Wake Stone still faced tough times. Pinning early expansion hopes on what was to have been Carolina Power & Light Co.’s billion dollar, four reactor Shearon Harris nuclear plant in southern Wake, the company opened its second quarry, in Moncure in 1975. Six years later, the power company scrapped three of the reactors, and Wake Stone shut down it’s quarry. It reopened it in 1987, when development around Jordan Lake reheated demand.

In 1982, after two years of angry encounters with environmentalists and appeals to state mining officials, Wake Stone broke ground on a third quarry, in Cary, south-west of Raleigh. It had been a bruising fight, pitting the company against, among others, Gov. Jim Hunt, who opposed it on grounds of noise, truck traffic and potential runoff.

“The problem with quarries is everybody needs them, but nobody wants them,” says Larry Quinlivan, marketing director for the National Stone Association trade group in Washington. Opposition dogs the industry. Martin Marietta, for example, recently abandoned a potential Charlotte site after a four-year battle. Wake Stone sizes up opposition before going ahead with a new site. If it decides to press on, it has a weapon: Its head-quarters adjoining the Knightdale quarry.

Built in the style of low-country plantation homes, the spotless, white frame house, with dormers, board porch and manicured grounds, is a standout among strips of shops and fast-food restaurants. Through the window behind Johnny Bratton’s desk, horses can be spied grazing. The quarry, screened by trees and earthen berms, can’t be seen. “When somebody says, ‘We don’t want a quarry for a neighbor, we bring them here and say, ‘Would you really mind this next door?’ ” Oxholm says.

The quarry in Cary is a study in contrasts. Drills bore blast holes into gray granite, and powerful ammonium nitrate charges rip the rock into desk size boulders. This is less than a mile from SAS Institute Inc., where 2,200 people develop software. Crabtree Creek flows nearby, and hikers walk the adjoining 5,400-acre Umstead State Park, some on trails of stone donated by Wake Stone. One of Johnny Brattons brothers is on the park advisory board. “They’ve been good neighbors,” says Martha Woods, park superintendent. “There are things that can’t be avoided trucks in and out but with the berms and shields they’ve built, you don’t see them.’

In 1984, in the prime of health, John Bratton gave his stock in Wake Stone equally to his seven children, but with strings attached. Johnny Bratton and his two brothers, who run the company, got shares with voting rights. Their sisters got nonvoting shares, with provisions that let them borrow against their stock and sell back shares at fair value. By granting the stock to his children before his death, Bratton sidestepped a common threat to family businesses: inheritance taxes, which can force sell-offs.

“Most family businesses never even make it to the second generation, ” Oxholm says. “By the time you get to the third and fourth generations, it gets very much fractured.” He is already working with the second generation on ways to minimize inheritance taxes and perpetuate Bratton ownership. “Family members realize that in selling out, every- thing goes away, and all you’re left with is cash or stock in a competitor.”

As his father did to him more than a decade ago, Johnny Bratton is gradually passing the reins to his younger brothers. Ted Bratton, 43, recently succeeded him as president and chief operating officer; and Sam Bratton, 33, is vice president for real estate. Their nephew Al Parker, 31, is an assistant superintendent. Each quarter, the family gathers for board meetings. “I wouldn’t say it’s mandatory, but we strongly urge everybody to come,” Johnny Bratton says. “It keeps them in touch and involved, and it gives us a chance to answer questions.”

Wake Stone has what amounts to an extended family. Holt Browning, construction vice president, has been there virtually from the beginning. Poole, a fraternity brother of Johnny Bratton’s at UNC and former N.C. State dean of students, came soon after. Oxholm, the accountant, joined in 1985, having served as the company’s account executive at KPMG Peat Marwick.

The company has retained employees with good pay for the industry. A truck driver, the lowest paid quarry job, typically earns $40,000 a year, including overtime, and benefits equal to 45% to 50% of wages. Industry sources say the company’s compensation packages are 10% more than bigger competitors.

Looking up from the bottom of the Knightdale pit, Johnny Bratton is the equivalent of 20 stories below where he and his father stood in 1970. In quarrying, the rock in a site like this is virtually inexhaustible. The limiting factor? When it gets so deep it costs more to move it out than it’s worth.

What Wake Stone can do, though, is make the hole wider, which is what it’s doing in Knightdale and two other quarries. It plans to add two more at undisclosed sites in the next decade. Unlike the shoestring it started with, its revenues are “perfectly adequate” for long-term survival, analyst Kasprzak says. Its volume in excess of 5 million tons a year makes it one of the top 40 aggregate producers nationwide.

On the road leaving the Knightdale quarry, Bratton stops his Land Rover at an office where trucks pause on scales to have their loads weighed. “We built it to look like the little tenant house we started in,” he says – a reminder of Wake Stone’s roots.

Edward Martin is a Charlotte-based freelance writer.